Therapists are often reluctant to see clients who just kicked their addiction. We know therapy can be wrenchingly difficult. We worry we’ll trigger a relapse if we see someone before they’re firmly grounded in sobriety. Maybe we shouldn’t.

A new study from University of South Wales researcher Katherine L Mills and her team tested their program, COPE: Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Substance Use Disorders Using Prolonged Exposure. As the name makes clear, COPE combines addiction treatment with prolonged exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Most would fear the grueling exposure process would cause the clients to relapse. It didn’t. After nine months, the COPE group and an addiction-treatment-only control group both saw the same decline in substance dependence. Among those who were still addicted, both groups’ members saw their addiction grow less intense by roughly the same amount. The only statistically significant difference between groups? Those in the COPE group had significantly lower rates of post-traumatic symptoms.

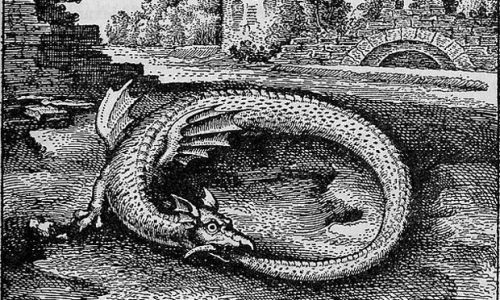

Critics have rapped the study for comparatively small effect-sizes. One would suggest they’ve missed the point. Dually-diagnosed clients can feel like Ouroboros – the mythical serpent forever swallowing its’ own tail. Alcohol and other drugs might be their only way to cope with emotional problems, even while their addiction makes those problems worse. Emotional pain and the struggles of recovery may be the right choice, but it’s a hard choice when the option is to get wasted one more time. In this study, even those clients who weren’t fully abstinent saw their PTSD symptoms dwindle.

The authors are clear that a client can’t get blotto every day and still get somewhere in therapy. They do say:

“These findings challenge the widely held view that patients need to be abstinent before any trauma work, let alone prolonged exposure therapy, is commenced. Although we agree that patients need to show some improvement in their substance use and an ability to use alternative coping strategies before prolonged exposure therapy is initiated, findings from the present study demonstrate that abstinence is not required.”

The fact these clients improved without firmly-established sobriety, some without even being fully abstinent, is more significant than the extent to which they recovered. More studies on therapy with the recently-sober, please.

Citation:

Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AL, Hopwood S, Sannibale C, Barrett EL, Merz S, Rosenfeld J, Ewer PL Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. [Journal Article, Randomized Controlled Trial, Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] JAMA 2012 Aug 15; 308(7):690-9.

@ 2012 Jonathan Miller All Rights Reserved